On 4 June 2021, the EU Commission adopted the final Implementing Decision (EU) 2021/914 setting out new standard contractual clauses for transfers of personal data to countries outside the EU/EEA1 (i.e. “third countries”).

These new standard contractual clauses (the “SCCs”) have been eagerly awaited by practitioners in the sector to replace the previous ones i.e. the “old SCCs” that were adopted in 2001, 2004 and 2010 respectively, which were based on the now repealed Directive 95/46/EC.

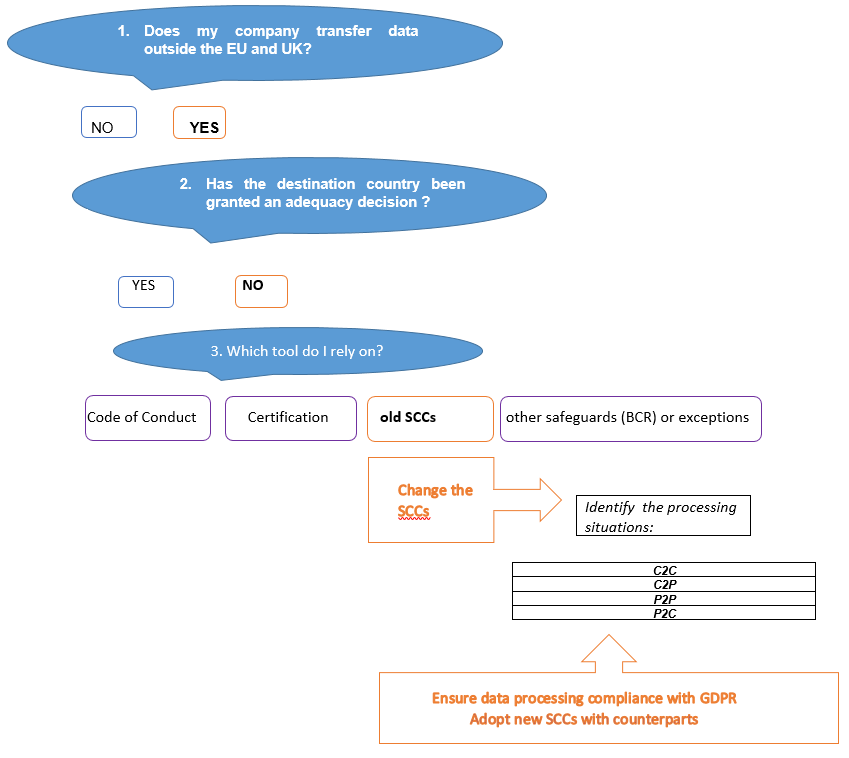

Here are some clarifications on what you need to know about the new SCCs and what you should do.

OLD SCCs:

In principle, the transfer of personal data to third countries that have not been recognised by the European Commission as providing an adequate level of protection of personal data is prohibited.

However, data exporters may proceed to such a transfer if they implement appropriate safeguards.

Among the recognised – and, in practice, the most used – appropriate safeguards, the data exporter may enter into an agreement containing the old SCCs adopted by the EU Commission with the data importer located in a third country.

However, since the so-called “Schrems II” ruling by the European Court of Justice, the old SCCs are under scrutiny. Indeed, the Court ruled that the old SCCs were valid but added a significant condition:

- data exporters have the obligation to ensure that the data subjects whose personal data are transferred are granted a level of personal data protection in the importing third country essentially equivalent to the one afforded by the GDPR;

- if necessary, data exporters shall implement additional measures to ensure such a level of personal data protection.

Failing that, data exporters shall not transfer personal data or at least suspend their transfer.

NEW SCCs: GLOBAL CHANGES IN PERSPECTIVE

The SCCs bring about a number of changes with practical implications, which we have summarised as follows:

1. Modular Approach of the SCCs: Different situations in one set.

The SCCs have now been drafted to cover different processing situations, offering four different modules. This is a different approach from the old SCCs that provided two different sets of clauses only governing processing situations where data controllers were transferring personal data (transfers from a controller to another controller and transfer from a controller to a processor respectively).

The SCCs now encompass a larger number of processing situations, making them more flexible to use, including:

- transfers from a controller to another controller (“C2C”);

- transfers from a controller to another processor (“C2P”);

- transfers from a processor to another processor (“P2P”);

- transfers from a processor to another controller (“P2C”).

2. Docking Clause, Third-Party Beneficiary Clauses and Data Processing Agreement.

The SCCs considerably ease a number of practical formalities, such as:

(i) the inclusion of an optional docking clause which allows new parties to be added to the SCCs during processing, making it easier to adapt to changes without having to re-sign documents;

(ii) the removal of the need to conclude an additional data processing agreement to govern the relationship between a processor and a controller, as all requirements foreseen under article 28 GDPR are now already reflected in the SCCs; and

(iii) the fact that the SCCs do not only relate to relationships between the contracting data exporter and data importer. Data subjects are also able to directly invoke most of the clauses in the SCCs against the data exporter and data importer.

3. GDPR AND SCCS: New Contents

Without being exhaustive, the SCCs’ content can be summarised as follow:

- Instructions: Where a transfer involves a processor, the processor undertakes to only act on the documented instructions of the controller and to inform the controller if it cannot follow those instructions2.

In a P2P3 relationship, a specific obligation lies on the exporting processor to inform the importing processor of the controller’s instructions as well as to inform the controller if the importing processor is not able to follow the controller’s instructions. It therefore acts as a sort of intermediary between the controller and the importer.

In a P2C4 relationship, the processor is also tied to the documented instructions of the importing controller. However, it must notify the controller if it is unable to follow its instructions and the controller must not give instructions contrary to the provisions of the GDPR.

- Purpose limitation: Purpose limitation is one of the fundamental principles of the GDPR, stating that personal data may only be collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes.

In the SCCs, where the importer is a processor, it must only process personal data for the specific purposes included in an Appendix to be completed by the parties.

However, the importer has a bit more freedom where it acts as a controller. In C2C5 relationships, the obligation is limited to processing personal data in a manner that is not incompatible with the purposes specified in the Appendix and it may rely on certain exceptions (such as the consent of the data subject to processing for different purposes).

In a P2C relationship, there are no specific restrictions on the importing controller, who is free to choose its own purposes for the processing of personal data.

- Transparency: data subjects must be aware of the transfer of their personal data.

In that respect, all of the SCCs modules (with the exception of the one governing P2C relationships, which has no specific provisions in this respect) specify that the SCCs shall be made available to data subjects on request.

In a C2C relationship, the transparency obligation is much broader. The importer must inform data subject of its identity and contact details, the categories of personal data processed, of their right to obtain a copy of the SCCs and various additional information where an onward transfer is planned.

- Accuracy: The accuracy of personal data must be ensured as per the relevant principle in the GDPR.

In a C2C relationship, both parties are required to correct inaccuracies and shall inform each other of such inaccuracies. Where the importer is a processor, it is required to notify the controller of any inaccuracies. In this case, the correction action must be carried out by the controller with, if necessary, the help of the processor.

In a P2C relationship, however, there are no specific provisions on accuracy of data.

- Storage limitation: According to the SCCs, the importer of data must also respect the principle of storage limitation.

In a P2C relationship, there are no specific provisions on this subject, the importing controller being then free to set the duration it sees fit for the processing of personal data.

- Security obligations: the SCCs include obligations to secure the transfer of personal data.

In this respect, Annex II must be completed by the parties to the SCCs, which describes the security measures to be implemented by the data importer.

In a C2C relationship, the importing controller’s obligations are far more wide ranging and include the obligation to report a breach directly not only to the exporting controller, but also to the supervisory authority or the data subjects, as the case may be.

On the contrary, the obligations are less stringent in a P2C relationship, the security obligations being limited to data transmission, confidentiality obligations and assisting the importing data controller in ensuring security. It should be noted that where sensitive data are processed, the parties shall document specific restrictions or safeguards to secure the transfer of personal data.

- Onward transfers: the SCCs deal with onward transfers of personal data to another entity located in a third country.

Such transfers are possible under the condition that the other entity adheres to the SCCs (using the appropriate module) or the transfer is subject to the appropriate safeguards described under the GDPR. Other grounds for transfers may also be invoked (for example depending on the situation: explicit consent of the data subject or defending legal claims).

In a P2C relationship, onward transfers are not further regulated.

- Accountability: The parties must be able to demonstrate compliance with their obligations under the SCCs at any time, thus extending the general accountability obligations applicable under the GDPR.

- Data subject rights: Data subject rights are also included in the SCCs.

In a C2C relationship, the controlling importer must deal with data subject rights requests. However, several rights are excluded, such as the right to data portability and the right to object to processing based on legitimate interests.

In a P2C relationship, each party shall mutually assist each other in responding to data subjects’ requests. Where the importer is also a data processor, it must notify the controller of the data subject request and help them deal with it.

- Schrems II decision :

The new SCCs have been drafted to take full account of Schrems II requirements i.e. the parties warrant in the SCCs that they have no reason to believe that the laws and practices in the third country of destination applicable to the processing of the personal data prevent the data importer from fulfilling its obligations under the SCCs. In their assessments of the laws and practices in the third country, the parties are required to take into account several criteria6.

WHAT SHOULD I DO ?

TRANSFER OF PERSONAL DATA OUTSIDE THE EU AND UK CHECKLIST :

4. WHEN ? NO TIME TO LOSE !

The Implementing Decision of the EU Commission is effective as of 27 June 2021 and the new SCCs may be used from this date.

The old SCCs may still be used until 27 September 2021 but will be valid only until 27 September 2022. Therefore, companies relying on the old SCCs for international transfers should now consider entering into the new SCCs.

1 On28 June 2021, the European Commission officially adopted an adequacy decision for the UK as a third country, so as to allow free flow of personal data. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_3183

2 obligation also included under article 28 of the GDPR.

3 P2P: processor to processor

4 P2C: processor to controller

5 C2C: controller to controller

6 EDPB published useful recommendations on 18 June 2021 to perform data transfer impact assessments: Recommendations 01/2020 on measures that supplement transfer tools to ensure compliance with the EU level of protection of personal data

Categories

AllLegal Topics

Banking & Finance

Business & Commercial

Corporate & M&A

Employment, Pensions & Immigration

Insolvency and restructuring desk

Insurance

Litigation & Dispute Resolution

Media, Data & Technologies

Real Estate, Construction & Urban Planning

Tax & Estate Planning

MOLITOR firm news