FROM MINIMAL RISK TO PROHIBITED PRACTICES: THE AI ACT RISK SPECTRUM FOR AI SYSTEMS

Join us as we uncover the latest insights into the European Union’s (the ‘EU’) ground-breaking Artificial Intelligence Act, in the wake of the leak of its most recent consolidated version on 26 January 2024 [i]. We delve herein into the core objectives, risk-based categorisation, and key provisions of this text, originally proposed by the European Commission on 21 April 2021 and now nearing adoption (the ‘AI Act’).

Starting with its primary objective, the AI Act aims to enhance the functioning of the internal market by establishing a uniform legal framework for the development, marketing, and use of artificial intelligence systems (the ‘AI systems’) within the EU. This framework is to be applied in accordance with EU values, to ensure a high level of protection of health, safety and fundamental rights enshrined in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU.

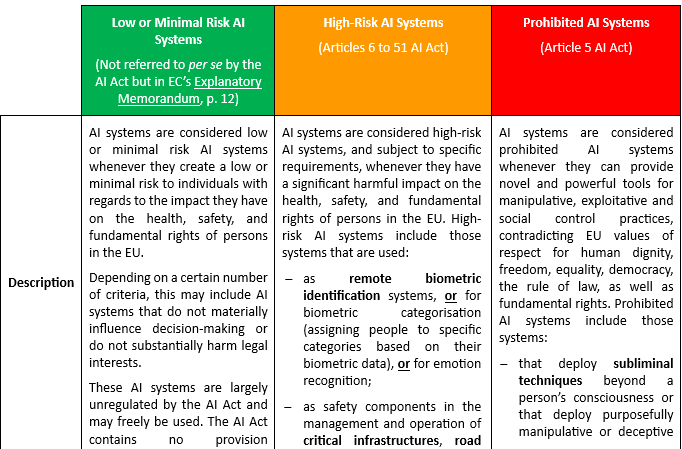

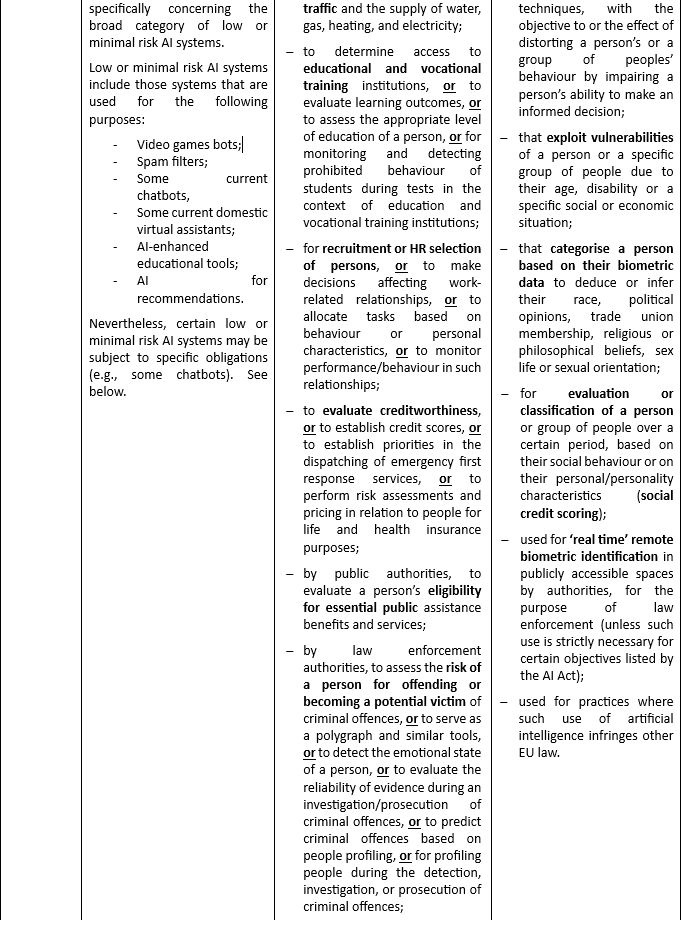

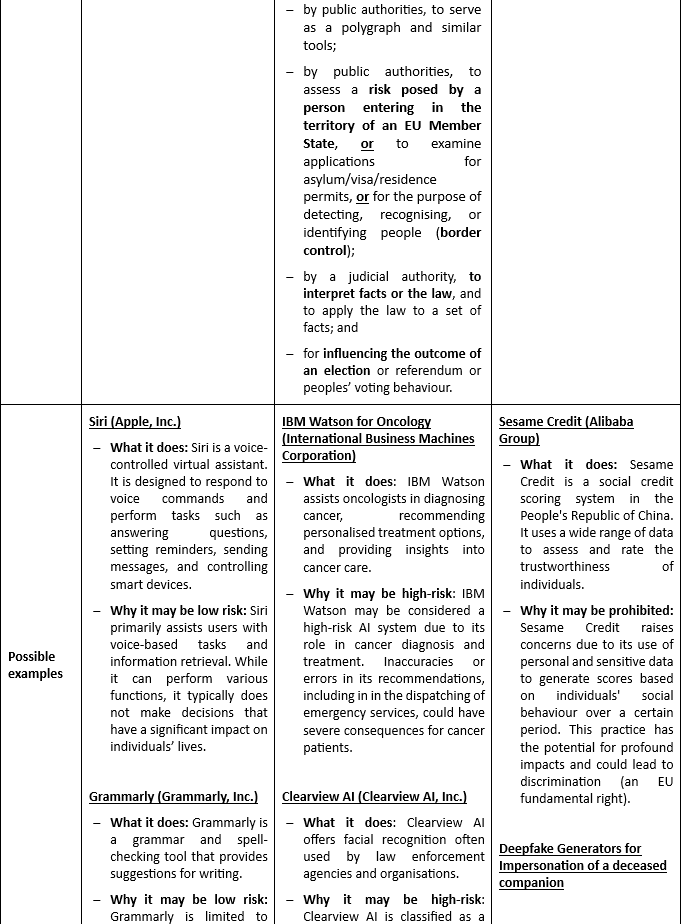

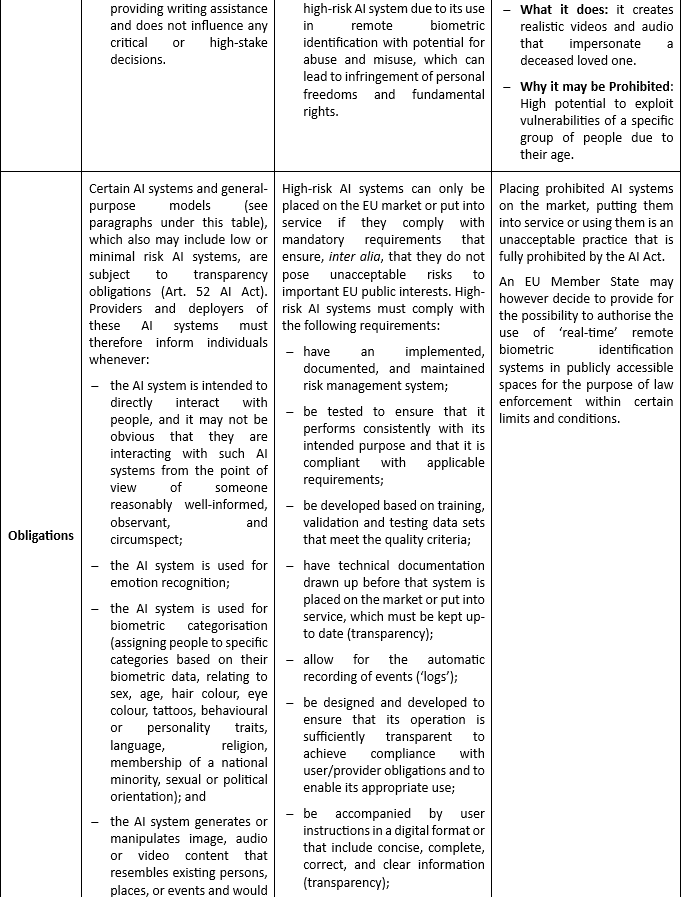

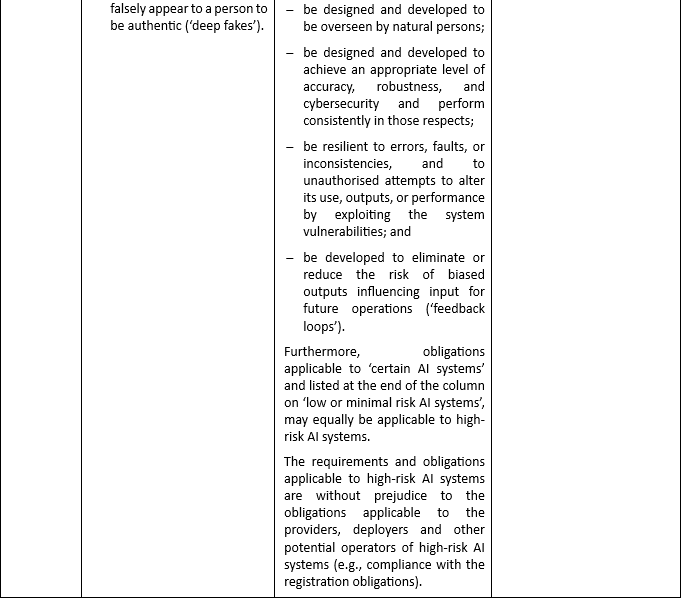

The AI Act introduces a risk-based approach for AI systems, similar to the GDPR’s data protection rules. This approach distinguishes three AI systems, based on the risk posed by their usage: Low or Minimal Risk AI Systems, High-Risk AI Systems, and Prohibited (or unacceptable) AI Systems. Occasionally, a fourth level is also mentioned in some papers published online: the ‘transparency risk’ or ‘limited risk’.

This risk differentiation stands out from Recital (14) of the AI Act, which currently states the following:

“It is therefore necessary to prohibit certain unacceptable artificial intelligence practices, to lay down requirements for high-risk AI systems and obligations for the relevant operators, and to lay down transparency obligations for certain AI systems”.

Below is a table detailing the three risk levels of AI systems, along with examples of AI systems for each risk level, and listing some requirements and obligations associated with each of those levels.

The AI Act also briefly touches upon the so-called general-purpose AI systems.

These AI systems are based on or integrate a general-purpose AI model with the capability of serving a variety of purposes (Article 3(44e) AI Act; Recital (60d) AI Act). However, the AI Act contains no specific requirement or obligation for general-purpose AI systems. Instead, it focuses on general-purpose AI models, which serve as a foundation of these general-purpose AI systems. This may include some of OpenAI’s ChatGPT models.

A general-purpose AI model may be placed on the market in various ways, including through libraries, application programming interfaces (APIs) or as a direct download (Recital (60a) AI Act). They allow for flexible generation of content (such as text, audio, images, or video) and can readily accommodate a wide range of tasks (Recital (60c) AI Act).

General-purpose AI models are essential components of some AI systems, but they do not constitute AI systems on their own – notably because they lack further components to be considered as such, for example, a user interface (Recital (60a) AI Act). Therefore, contrary to what some papers may suggest, they are not inherently an AI system, nor do they fall in one of the existing three risk categories of AI systems.

Providers of general-purpose AI models are nevertheless subject to specific requirements and obligations (Article 52c AI Act), including draw up technical documentation, a policy to respect EU copyright law, and a detailed summary about the content used for training. Furthermore, since general-purpose AI models may be integrated or form part of many different AI systems (including high-risk AI systems), they may pose a systemic risk. In such cases where the AI model meets the criteria to be classified as having a systemic risk, providers are subject to additional obligations (Articles 52d and 52e AI Act).

When the provider of a general-purpose AI model integrates their model into their own AI system, the obligations provided for general-purpose AI models may apply in addition to those for AI systems (Recital (60a) AI Act).

In conclusion, the EU’s AI Act represents a significant step forward in the regulation of AI systems. Its goal is to bring the rules for the development, marketing, and use of these systems into uniformity within the EU while maintaining a high level of protection for health, safety, and fundamental rights of EU citizens.

It also presents new opportunities and challenges, for which MOLITOR’s Media, Data, Technology, and IP team can offer its comprehensive expertise. On the one hand, we can assist clients in understanding and complying with the AI Act, particularly with high-risk AI systems and transparency obligations. On the other hand, we can assist you in either exercising your personal data rights or complying with the GDPR’s obligations relating to personal data in the AI field. This includes the drafting of terms and conditions for the deployment and usage of AI systems, as well as privacy policies and data processing agreements.

Please contact us should you require our assistance in complying with and navigating the complexities of AI regulations.

[i] Consolidated version dated 26 January 2024 of the Artificial Intelligence Act

IP News: All that glitters is not gold

While glitter may be perfect for festive make-up and adds a bit of shine to our lives, these sparkles are extremely harmful to the environment. Regulations governing cosmetics in the European Union are set to evolve, bringing new compliance obligations. Our team recognizes the challenges this transition poses for the cosmetic industry and is ready to support you in this context.

For several years, the Council has urged the Commission to propose measures to reduce plastic debris in the marine environment, including banning polymers in cosmetic products[1]. In response, the Commission adopted a plastics strategy in January 2018[2], reaffirmed in the European Green Deal[3] in December 2019, the new Circular Economy Action Plan in March 2020[4], and the Zero Pollution Action Plan in May 2021[5], with the goal of reducing microplastic pollution by 30% by 2030.

To combat this pollution whilst preserving market unity, the Commission asked the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) to assess the risks related to microplastics which are intentionally added to products[6]. ECHA’s findings advocated the introduction of a limitation[7], and armed with this scientific data, the Commission proposed a restriction under the REACH regulation[8]. This proposal garnered support from EU Member States, passed through the European Parliament and Council successfully and was ultimately adopted[9].

On 25 September 2023[10], the European Commission took a significant step towards environmental protection by adopting measures restricting the intentional use of microplastics[11] in products. This directly impacts our cosmetics, especially those using microplastics for various purposes such as exfoliants (microbeads) or for specific texture, fragrance, or colour properties[12].

In practical terms, as of 16 October 2023[13], loose glitter and products containing certain types of microbeads can no longer be sold in the European Union. Unlike our German neighbours, there’s no need to rush to stock up on glitter[14]. In addition to the possibility of sourcing from the United Kingdom, where the ban does not apply, various ecological alternatives exist.

As for the glitter in our make-up products, lipsticks, and nail polish, the sales ban will take effect after an extended period of 12 years[15]. Due to the costs of formulating these products and their less significant contribution to overall plastic emissions, the 12-year transitional period before they are banned is designed to ensure an adequate timeframe for the development of suitable alternatives while limiting costs for the industry.

As mentioned earlier, the EU’s goal is not to eliminate all glitter but rather to substitute it with eco-friendly alternatives, in line with the aim to make Europe the first carbon-neutral continent by 2050[16]. In this context, we offer specific expertise to guide you in adapting to the new regulations while preserving your competitiveness. From advising on developing environmentally-friendly alternatives to ensuring compliance with European standards, we can help you with ensuring that your company’s star shines bright in this glittering world. So, ready to shine while staying green?

The MOLITOR Media, Data, Technologies & IP team wishes you a Merry Christmas and a happy holiday season!

Virginie, Caroline and Ruben

[1] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/24073/st_7348_2017_rev_1_en.pdf

[2] Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European

Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A European Strategy for Plastics

in a Circular Economy (COM/2018/028 final).

[3] Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council,

the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: The European Green

Deal (COM/2019/640 final).

[4] Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European

Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A new Circular Economy Action

Plan for a cleaner and more competitive Europe (COM/2020/98 final).

[5] Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European

Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Pathway to a Healthy Planet for

All EU Action Plan: ‘Towards Zero Pollution for Air, Water and Soil’ (COM/2021/400 final).

[6]Commission request of 9 November 2017 asking the European Chemicals Agency to prepare a

restriction proposal conforming to the requirements of Annex XVII to REACH.

https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/5c8be037-3f81-266a-d71b-1a67ec01cbf9

[7]https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/db081bde-ea3e-ab53-3135-8aaffe66d0cb

[8] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/FR/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02006R1907-20140410

[9]https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-09/C_2023_6419_F1_COMMISSION_REGULATION_UNDER_ECT_EN_V5_P1_2620969.PDF

[10]https://france.representation.ec.europa.eu/informations/protection-de-lenvironnement-et-de-la-sante-la-commission-adopte-des-mesures-pour-limiter-les-2023-09-25_fr

[11] Microplastics include all organic particles of synthetic polymers less than 5 mm in size, insoluble and resistant to degradation.

[12]Recital 21 – C(2023) 6419 – Commission Regulation (EU) …/… amending Annex XVII to Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) as regards synthetic polymer microparticles.

[13]Article 2 – C(2023) 6419 – Commission Regulation (EU) …/… amending Annex XVII to Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) as regards synthetic polymer microparticles.

[14] https://www.forbes.fr/politique/interdiction-des-paillettes-en-europe-lue-sattaque-aux-plastiques/

[15]Recital 35 – C(2023) 6419 – Commission Regulation (EU) …/… amending Annex XVII to Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) as regards synthetic polymer microparticles

[16]https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/green-deal/#:~:text=The%20European%20Green%20Deal%20is%20a%20package%20of%20policy%20initiatives,a%20modern%20and%20competitive%20economy.

IP News : Où sont passées les paillettes ?

Les paillettes, idéales pour un make-up festif, voient leur éclat s’obscurcir dans l’Union Européenne. Si les paillettes ajoutent un peu d’éclat à notre vie, ces pépites scintillantes sont extrêmement néfastes pour l’environnement.

La réglementation cosmétique à vocation à évoluer et occasionnera de nouvelles obligations de mise en conformité. Notre équipe reconnaît les défis que cette transition impliquera pour les acteurs de l’industrie cosmétique et répondra présente pour vous accompagner dans ce contexte.

Depuis plusieurs années, le Conseil a incité la Commission à proposer des mesures visant à réduire les rejets de débris plastiques dans le milieu marin, notamment en interdisant les polymères dans les produits cosmétiques[1]. En réponse, la Commission a adopté une stratégie sur les plastiques en janvier 2018[2], réaffirmée dans le Green Deal Européen[3] en décembre 2019, du nouveau plan d’action pour l’économie circulaire en mars 2020[4] et du plan d’action pour une pollution zéro en mai 2021[5], fixant l’objectif de réduire la pollution par les microplastiques de 30 % d’ici à 2030.

Pour mener cette lutte tout en préservant l’unité du marché, la Commission a confié à l’Agence européenne des produits chimiques (ECHA) le mandat d’évaluer les risques liés aux microplastiques intentionnellement ajoutés aux produits[6]. Les conclusions de l’ECHA ont plaidé en faveur de leur restriction[7], et la Commission, armée de ces données scientifiques, a formulé une proposition de restriction en vertu du règlement REACH[8]. Cette proposition a obtenu le soutien des États membres de l’UE, a franchi avec succès l’examen du Parlement européen et du Conseil, pour finalement être adoptée[9].

Le 25 septembre 2023[10], la Commission Européenne a franchi une étape importante pour la protection environnementale en adoptant des mesures restreignant l’utilisation intentionnelle des microplastiques[11] dans les produits. Cela impacte directement nos cosmétiques, notamment ceux utilisant des microplastiques à des fins multiples, tels que les exfoliants (microbilles) ou pour des propriétés de texture, parfum, ou couleur spécifiques[12].

Concrètement, depuis le 16 octobre 2023[13], les paillettes en vrac[14] et les produits contenant certains types de microbilles ne peuvent plus être vendus dans l’Union Européenne. Contrairement à nos voisins allemands, pas besoin de se précipiter pour faire le plein de paillettes[15] : en plus de la possibilité d’approvisionnement au Royaume-Uni, où l’interdiction ne s’applique pas, diverses alternatives écologiques existent.

En ce qui concerne les paillettes présentes dans nos produits de maquillage, rouges à lèvres, et vernis à ongles, l’interdiction de vente prendra effet après une période plus étendue[16]. En raison des coûts de reformulation de ces produits et de leur contribution moindre aux émissions globales de plastiques, une période transitoire de 12 ans est accordée pour l’interdiction de la mise sur le marché de ces produits, assurant ainsi un délai adéquat pour le développement d’alternatives appropriées tout en limitant les coûts pour l’industrie.

Comme évoqué précédemment, l’objectif de l’Union Européenne n’est pas d’éliminer toutes les paillettes, mais plutôt de les substituer par des alternatives écologiques, alignées sur la volonté de faire de l’Europe le premier continent neutre en carbone d’ici 2050[17]. Dans ce contexte, nous offrons une expertise spécifique pour vous guider dans l’adaptation aux nouvelles réglementations, tout en préservant votre compétitivité. Du développement d’alternatives respectueuses de l’environnement à l’assurance de la conformité aux normes européennes, nous pouvons vous assister pour que votre entreprise demeure la star incontestée du monde pailleté. Alors, prêts à briller tout en restant green ?

L’équipe Media, Data, Technologies & IP de MOLITOR vous souhaite un joyeux Noël et de belles fêtes de fin d’année !

Virginie Caroline et Ruben.

[1] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/24073/st_7348_2017_rev_1_en.pdf

[2] Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European

Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A European Strategy for Plastics

in a Circular Economy (COM/2018/028 final).

[3] Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council,

the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: The European Green

Deal (COM/2019/640 final).

[4] Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European

Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A new Circular Economy Action

Plan for a cleaner and more competitive Europe (COM/2020/98 final).

[5] Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European

Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Pathway to a Healthy Planet for

All EU Action Plan: ‘Towards Zero Pollution for Air, Water and Soil’ (COM/2021/400 final).

[6] Commission request of 9 November 2017 asking the European Chemicals Agency to prepare a

restriction proposal conforming to the requirements of Annex XVII to REACH.

https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/5c8be037-3f81-266a-d71b-1a67ec01cbf9

[7] https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/db081bde-ea3e-ab53-3135-8aaffe66d0cb

[8] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/FR/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:02006R1907-20150601&from=FR

[9] https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-09/C_2023_6419_F1_COMMISSION_REGULATION_UNDER_ECT_EN_V5_P1_2620969.PDF

[10] https://france.representation.ec.europa.eu/informations/protection-de-lenvironnement-et-de-la-sante-la-commission-adopte-des-mesures-pour-limiter-les-2023-09-25_fr

[11] Les microplastiques englobent toutes les particules organiques de polymères synthétiques de moins de 5 mm, insolubles et résistantes à la dégradation.

[12] Considérant 21 – C(2023) 6419 – Commission Regulation (EU) …/… amending Annex XVII to Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) as regards synthetic polymer microparticles.

[13] Article 2 – C(2023) 6419 – Commission Regulation (EU) …/… amending Annex XVII to Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) as regards synthetic polymer microparticles.

[15] https://www.forbes.fr/politique/interdiction-des-paillettes-en-europe-lue-sattaque-aux-plastiques/

[16] Considérant 35 – C(2023) 6419 – Commission Regulation (EU) …/… amending Annex XVII to Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) as regards synthetic polymer microparticles

[17] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/green-deal/#:~:text=The%20European%20Green%20Deal%20is%20a%20package%20of%20policy%20initiatives,a%20modern%20and%20competitive%20economy.

Empowering Consumers for a Green Tomorrow

Towards sustainable choices: navigating the EU’s green transition strategies

Sustainability is a crucial asset for modern businesses, with 56% of European consumers being influenced by environmental factors to varying degrees when purchasing goods and services[1]. However, despite the emphasis on ecological considerations, misleading advertising remains a persistent concern for European consumers. This deceptive practice, known as greenwashing, involves organisations creating a false impression of ecological responsibility, often by using brand names or unsubstantiated environmental claims. Several fashion brands, including H&M[2], Nike[3], Boohoo, ASOS and Asda[4], have found themselves under the greenwashing radar in recent years. The increasing number of such cases indicate a pressing requirement for more straightforward guidelines for businesses and the legal system.

On 19 September 2023, the Council and the Parliament reached a provisional political agreement[5] on the proposal for a directive to empower consumers for a green transition. While the detailed content of this agreement is not yet available, it is anticipated the directive will enable the EU consumers to:

- Access Reliable Information: Consumers will have access to reliable information, facilitating informed decisions regarding making green choices;

- Protection Against Unfair Green Claims: Measures will be implemented to shield consumers against unfair green claims better; and

- Product Repairability Information: Consumers will receive improved information about the repairability of products before making a purchase.

Additionally, the directive will introduce a harmonised label displaying information about producers’ commercial durability guarantee.

The Council affirms that this compromise agreement seamlessly aligns with the core objectives outlined in the Commission’s initial proposal of 30 March 2022[6]. The proposal demonstrates a pivotal effort to bolster consumers’ rights by amending the unfair commercial practices directives (2005/29/CE[7]) and the consumer rights directive (2011/83/EU[8]), tailoring them to propel the green transition.

Rooted in the vision of a circular, clean, and sustainable European economy, these objectives empower consumers to make ecologically informed choices. This agreement signifies a significant stride toward cultivating a marketplace in which environmental awareness guides consumer decisions, marking a crucial advancement in pursuing an eco-conscious society.

Next steps: green consumer empowerment ahead

The Parliament and the Council must formally endorse and adopt the provisional agreement to complete the legislative process. The Parliament is anticipated to take a decision during a plenary session in November 2023. Subsequently, member states will have a two year period to transpose the directive into their national laws.

The interconnected initiatives driving sustainability

It is crucial to emphasise that this directive is not an isolated effort but is embedded within a broader framework of European initiatives. The proposal constitutes one of the initiatives outlined in the Commission’s 2020 New Consumer Agenda and 2020 Circular Economy Action Plan, building upon the principles of the European Green Deal. It operates within a comprehensive package of four proposals, complemented by the eco-design regulation[9] and the directive proposals addressing green claims[10] and the right to repair[11]. These initiatives represent a cohesive strategy to foster a sustainable, circular, and environmentally conscious European economy.

[1]European Commission, Key consumer data: The European Commission is providing new information to assess consumers’ needs in the Single Market and their response to multiple crises, 27 March 2023.

[2]https://www.thesustainablefashionforum.com/pages/hm-is-being-sued-for-misleading-sustainability-marketing-what-does-this-mean-for-the-future-of-greenwashing

[3] https://www.retaildive.com/news/nike-faces-lawsuit-greenwashing-claims/650282/

[4]https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/asos-boohoo-and-asda-greenwashing-investigation

[5]Council of the EU, Council and Parliament reach a provisional agreement to empower consumers for the green transition, Press release, 19 September 2023.

[6]https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-7808-2022-INIT/en/pdf

[7]Directive 2005/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2005, concerning unfair business-to-consumer commercial practices in the internal market and amending Council Directive 84/450/EEC, Directives 97/7/EC, 98/27/EC and 2002/65/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and Regulation (EC) No 2006/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council (‘Unfair Commercial Practices Directive’) (Text with EEA relevance).

[8]Directive 2011/83/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011, on consumer rights, amending Council Directive 93/13/EEC and Directive 1999/44/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and repealing Council Directive 85/577/EEC and Directive 97/7/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council Text with EEA relevance.

[9]https://environment.ec.europa.eu/publications/proposal-ecodesign-sustainable-products-regulation

[10]https://environment.ec.europa.eu/publications/proposal-directive-green-claims_en

[11]https://commission.europa.eu/law/law-topic/consumer-protection-law/consumer-contract-law/rules-promoting-repair-goods_en

AI Act and GDPR: managing the world of data in the world of privacy

Article published with INPLP.

Contrary to some persisting beliefs that the AI Act and GDPR are inherently incompatible, GDPR may in fact be interpreted in a way that concords with the purposes of the AI Act. Processing personal data through an artificial intelligence (AI) system’s algorithm triggers the application of GDPR.

I systems are designed to operate with a certain level of autonomy, that is, without human involvement (Recital (6) AI Act).

They infer how to achieve a given set of objectives without being explicitly programmed to attain it, thanks to machine learning, logic-based approaches and knowledge-based methods (Article 3 AI Act).

An AI system requires the training of a computational model to perform specific tasks or to make predictions based on data that has been collected, cleaned, normalised, extracted and validated.

Some AI systems may be trained with data to:

– play a board game,

– to drive vehicles,

– to execute simple voice commands, and

– to generate text-based content.

To that end, AI systems, particularly those rooted in deep learning, rely on vast amounts of data to efficiently:

– identify patterns,

– develop probabilistic models, and

– deliver accurate results.

Data used to train AI systems or provided to them as input often includes personal data, including sensitive personal data, which presents significant privacy concerns and must therefore be compliant with GDPR.

THE QUESTION WE MIGHT ASK IS WHETHER THE AI ACT AND GDPR ARE COMPATIBLE?

The current version of the AI Act explicitly provides that GDPR principles apply to training, validation, and testing datasets of AI systems (Recital (44a) AI Act). Moreover, it underscores that the AI Act in no way affects the obligations of AI providers/users as data controllers or processors (Recital (58a) AI Act). But it is a major challenge for AI system providers to comply with GDPR principles. We will mainly focus on the principle of lawfulness as an exercise to understand whether it is possible to comply with one key GDPR principle.

The principle of lawfulness essentially provides that personal data must be processed in a lawful, fair, and transparent manner (Art. 5.1(a) GDPR). Prior to undertaking data processing, any person or organisation (company, non-profit organisation, foundation, etc.) must therefore identify a legal basis for it from the six bases provided by the GDPR (Art. 6.1 GDPR):

– consent,

– performance of a contract,

– legal obligation,

– vital interests,

– public task, and

– legitimate interests.

Establishing a legal basis for processing personal data can give rise to a complex conundrum within the realm of AI.

(i) Processing based on ‘consent’ (Art. 6.1(a) GDPR): this is only an appropriate lawful basis if the data subject is genuinely offered control and a choice with regard to accepting or declining the terms offered, without any detriment.

The individual’s consent to the processing of their personal data is naturally a highly valued legal basis because it reflects the values of a democratic society. It may indeed seem reasonable to ask the data subject whether they wish to have their personal data processed by another entity.

However, within the context of AI systems:

– ensuring ‘informed consent’ may not always be viable, especially with regards to complex machine learning algorithms whose results are often generated through processes that are not yet fully understood (e.g., the “black box” problem).

– obtaining ‘unambiguous consent’ from every single data subject may also be an impractical approach because of the large datasets, of various categories, originating from countless sources. This issue is exacerbated when data has not been directly obtained from data subjects themselves but has been scraped from websites or obtained through an intermediary instead – including data pools.

– granting data subjects the ‘right to withdraw’: Managing and implementing this right can pose technical difficulties due to the vast quantities of words, images, or sounds. This complexity extends to the fact that each word is processed in a tokenized form within an AI system, either as a single element or broken into multiple separated elements, and only becomes correlated with others when vectorized in a pre-trained machine learning model.

(ii) The ‘performance of a contract’ (Art. 6.1(b) GDPR): this lawful basis for the processing of personal data could be a solution, particularly whenever an existing contract governs the relationship between the provider of an AI system and the end user.

(iii) A legal obligation to which the controller is subject (Art. 6.1(c) GDPR): this is, to the best of our knowledge, not a valid legal basis as there is no law yet requiring the data controller to use AI to meet its legal obligation.

(iv) Alternative legal basis may not always be valid. These specific legal bases require establishing the necessity of the processing for a specific aim that often remains unmet with AI-related processing (Art. 6.1(c), (d) & (e) GDPR).

A processing based on ‘public task’ or to protect ‘vital interests’ may not be valid, particularly when using AI systems for commercial purposes, for instance.

(v) More generally, providers of AI systems could potentially rely on the ‘legitimate interests’ legal basis as a last resort (Art. 6.1(f) GDPR).

This basis would require a careful assessment and may only apply when no other basis finds application (Recital (47) GDPR).

Furthermore, opting for this legal basis demands a careful balance between the interests of providers of AI systems and the data subject’s fundamental rights and freedoms (Art. 6.1(f) GDPR; Recital (47) GDPR).

In any event, an AI system cannot be trained and be designed to operate based on data collected illegally.

Personal data collected in violation of GDPR rules, or any data type that has been indiscriminately scraped from websites, in contravention of a website’s terms of use or of protected databases (see Directive 96/9/EC), could potentially lead to the AI system being banned.

The road to determining an appropriate legal basis for AI solution may be winding and tricky but it does not seem impossible – which is good news.

Other questions are also of great importance when analysing GDPR principles for AI systems. For example, the processing of personal data for purposes other than those for which the personal data have been collected is essential to AI (in particular, for statistical analytics), due to the vast and diverse repositories of data and methodologies deployed to discover correlations and/or potential causal relationships.

In the context of AI, compliance with GDPR principles is crucial to ensure ethical and legal personal data processing. The misuse or illegal collection of data may lead to serious consequences, including a potential prohibition of AI systems. It is also essential to balance the benefits of AI with the fundamental rights of data subjects to foster responsible development of AI and maintain the privacy and freedoms of individuals in the digital era.

ANELD Career Day 2023

Are you a law student looking for a #law career and #internship opportunities ?

As a proud partner of the @ANELD, our team will be present again this year at the ANELD Career Day on November 4 at the European Convention Center Luxembourg and will be glad to discuss with you about legal professions.

You can register here : https://www.linkedin.com/events/aneldcareerday20237108763188774481921/

IBA Annual Conference Paris 2023

Our team will be attending the IBA Annual Conference 2023 in Paris.

If you plan to attend and would like to exchange on Luxembourg legal opportunities and challenges, contact us at:

iba@molitorlegal.lu

Welcome to our new joiners!

Welcome to our new talents: Guillaume Roux (Senior Associate – Tax & Estate Planning), Katarzyna Prusak (Junior Associate – Employment, Pensions & Immigration), Caroline Gal (Associate – Media, Data, Technologies & IP), Ruben MENDES (Senior Associate – Media, Data, Technologies & IP) and Jiar Al-Zawity (Associate – German Desk).

We are delighted to have you as part of our dynamic team. Your diverse skills and unique experiences will undoubtedly enrich our work environment and contribute to our collective growth.

We firmly believe that teamwork is key to achieving the best outcomes and is the driving force behind our success.

Welcome aboard on this exciting journey towards excellence!

A new law to rule non-profit associations

On 23 September 2023, the law of 21 April 1928 on non-profit associations and foundations was repealed and replaced by the brand-new law of 7 August 2023.

1. Legal innovations

This new law notably includes certain changes for Luxembourg non-profit associations (ASBLs), the major ones being the following:

- It is no longer necessary to annually file changes to the ASBL’s members list with the registry of the civil court. It suffices to keep this list up-to-date at the ASBL’s registered office.

- Benefactors and honorary members have now a legal foundation with a new title of “membres adhérents”. Their rights and obligations are freely fixed by the articles.

- Board meetings may be held by phone or video conference. In addition, the articles of association may authorise unanimous written resolutions taken by all the directors.

- The articles of association may also authorise the attendance of general meetings by phone or video conference.

- The threshold above which a donation to an ASBL requires administrative authorisation has been raised to EUR 30,000. If the donation is made inter vivos by means of a bank transfer from a credit institution authorised to operate in an EU or EEA country, then no authorisation is required, regardless of the amount.

- Ownership of real estate not strictly necessary to achieve the ASBL’s purpose is now allowed.

- There will be a classification of ASBLs into 3 categories in order to determine the accounting regime applicable to them:

- Small ASBLs (less than 3 employees, max. EUR 50,000 annual revenue, max. EUR 100,000 in assets) can continue to prepare simplified accounts, showing all revenue and expenditure.

- Medium-sized ASBLs (max. 15 employees, max. EUR 1,000,000 annual revenue, max. EUR 3,000,000 in assets) must keep double-entry accounts, just like most commercial companies.

- Large ASBLs (more than 15 employees, more than EUR 1,000,000 annual revenue, more than EUR 3,000,000 in assets) and all ASBLs recognised as being of public interest must not only keep double-entry accounts, but they must also have their annual accounts audited by an independent auditor.

In order to establish in which category a given ASBL fits, it depends on whether, at the end of two consecutive financial years, it exceeds the numerical limits of at least two of the three criteria mentioned above (i.e. number of full-time employees, level of total annual revenue, and total assets at the end of the fiscal year).

2. Transition period

ASBLs formed before the new law came into force have until 23 September 2025 to adapt their articles of association to the new legal provisions. In the meantime, an ASBL which does not adapt its articles will until the said deadline continue to be governed by the former law of 21 April 1928, which means that the application of the new accounting rules may thus be postponed to the financial year 2026, but in such case the flexible meeting rules will also not apply before the deadline.

Version française disponible ici.